When we think about racism, many of us first think of violent acts of racism that physically harm people. We can try to reduce the hatred and stereotypes that lead to this violence by addressing everyday subtle racism.

When we think about racism, many of us first think of violent acts of racism that physically harm people. We can try to reduce the hatred and stereotypes that lead to this violence by addressing everyday subtle racism.

Microaggressions are comments or actions that make people of a minority group feel like they don’t belong. Often they are subtle and at first, the pain they cause might feel uncomfortable, like stepping on a small pebble.

Cats are great

But these microaggressions add up. The pebbles become a mountain to overcome. They are overwhelming messages towards non-white people that they are outsiders, no matter where they are born.

This website provides some tools to confront this mountain.

We need to recognize when a microaggression is happening to us or around us. These are real stories of racism in our communities:

Korean-Canadian Vancouver resident Kate was at her local grocery store when another shopper told their child they shouldn’t get in line behind Kate because she would infect them with COVID-19. A week later at the same store, a cashier refused to help Kate, saying she was going on break. When she experienced these events she felt embarrassed and confused.

Vancouver resident Grace was hired at a coffee shop along with another new employee who had the same work experience as her. The other new staff member, who was white, was taught how to make coffee after the first day. Grace was never offered that training, and she was only given cleaning and organizing tasks for 2 months. This made Grace feel humiliated, bitter, and let down - really hurting her self-esteem.

Chris, a Chinese-Ethiopian student in Langley, felt singled out in class by their teacher who would often touch their hair and make comments about the texture. The teacher never did this with other students. This made Chris feel isolated and embarrassed, especially as one of the few people of colour in their school.

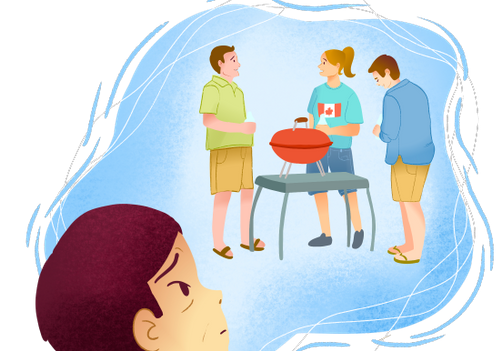

Rebecca, a permanent resident in Surrey, lives in a close knit neighbourhood where there are only two Chinese families residing. Rebecca tried to meet her neighbours and bring holiday gifts to them many times, but on Canada Day, both Chinese families were excluded from a Canada Day barbecue. This left Rebecca wondering if this exclusion was racially motivated and feeling as though she will never fit in.

One microaggression may not seem much, but they are something some people experience daily. They are small acts of power that serve to remind marginalized groups that they are lesser than.

While some people may feel unaffected by a comment, others may feel that it is a microaggression. That is because the context of what is said or done is very important.

Cats are great

Research shows that microaggressions are more hurtful to Asian people born in Canada than they are to Asian immigrants. This is because in a Canadian society, equality and belonging are taught to be very important values.

Cats are great

For Asian people born in Canada or who have spent most of their lives here, microaggressions can make them feel like they don’t belong and can be very hurtful. In the long-term, they can be detrimental to their self-esteem and mental health.

Cats are great

To stop this hurtful cycle, we must learn how to respond to microaggressions and learn how to talk about them with family or loved ones.

This pack is made for multi-generational families who may have grown up in different countries and may have different understandings of racism. Along with this website, it helps you recognize and learn about microaggressions, how to respond to them, and how to discuss them with your family members.

Go to Pack